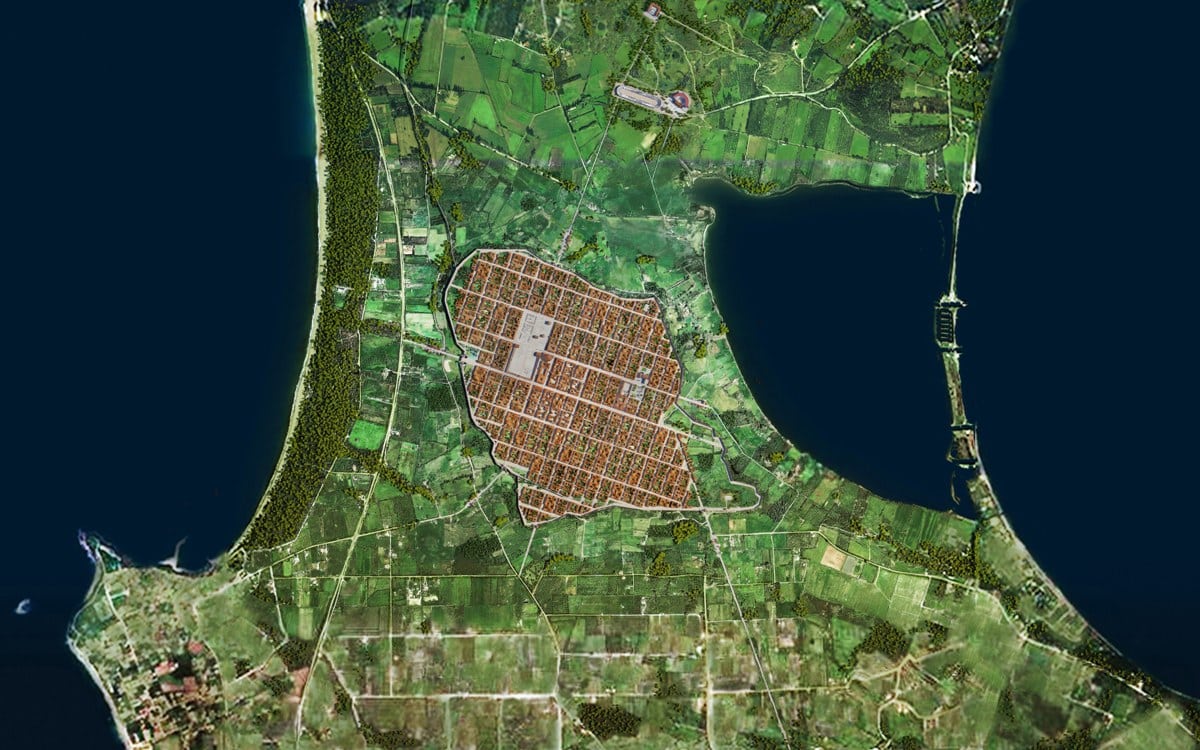

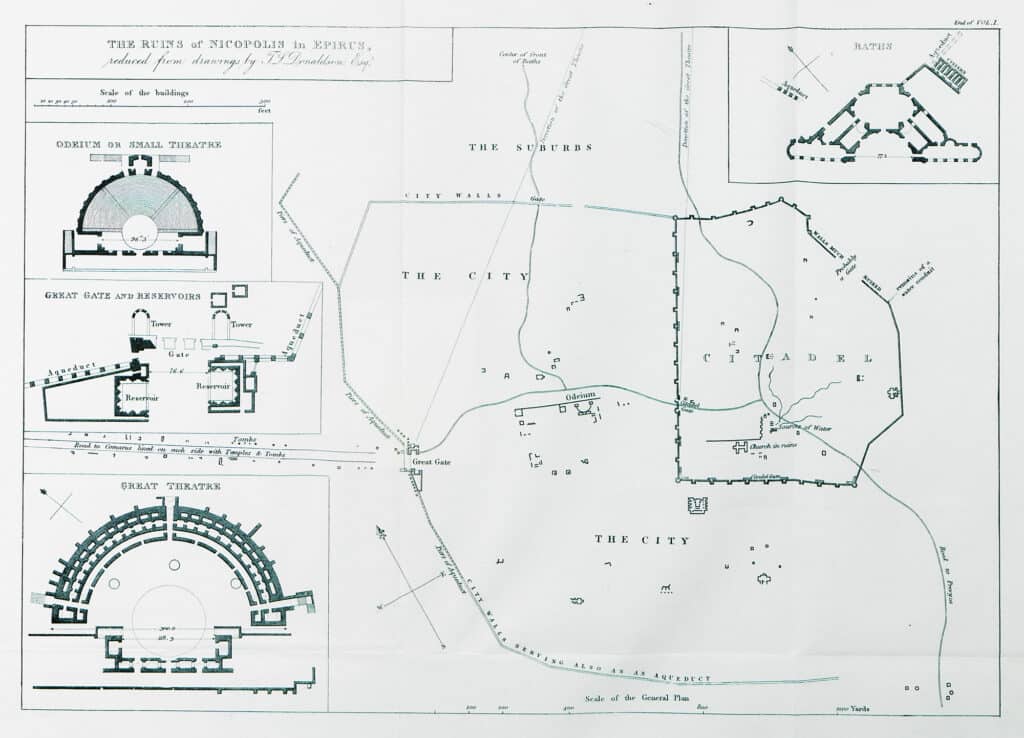

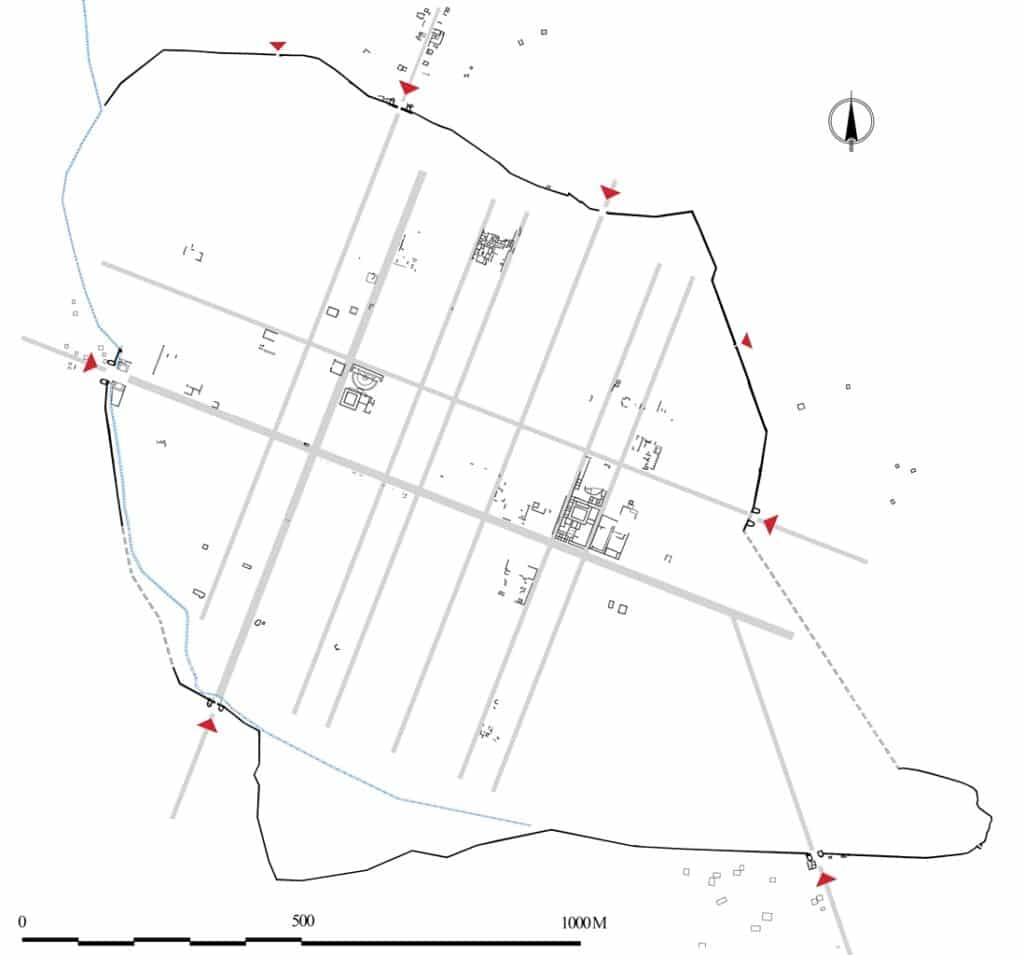

The walls of Nicopolis belonged to the Augustan-era building program and present a uniform image in terms of building technique and materials. They were made with a poured concrete core and faced in large bricks of two sizes in successive courses. The walls are 2.50 meters thick throughout their length, apart from at points where corners and the gates were formed, whose thickness increased to 4.60 meters. They have a polygonal plan and enclose an area of 14,000 stremmata (1400 hectares). Their perimeter is estimated at 5000 meters.

The wall’s course may be followed with precision along its north and south sides. Remains of the south part of the west wall (i.e. south of the main West Gate) are preserved from the west side, while north of this gate no traces of it have been found. In all probability, this part was never completed, and for this reason later the intervals between the piers of the Aqueduct, which ran parallel to the imaginary course of the wall, were later sealed shut with makeshift walls. This intervention between the piers was apparently imposed by some emergency—probably, an enemy invasion—as showed also by the building material employed, which included spolia (architectural members from various buildings, fragments of statues, even fragments of inscriptions). From the east wall of the Roman fortifications, only the north part of the East Gate, atop which the Early Christian wall was late built, survives. South of the East Gate the wall’s course is unclear.

Although they represented a major and expensive project, the rules of fortification architecture were not consistently applied to the Augustan walls (e.g., the towers were sparsely-set), which lends them more of a decorative than defensive character. Augustus’s reorganization of the army and the peace that prevailed throughout the vast empire after the battle of Actium—the vaunted Pax Romana—ensured Nicopolis’s protection and made a fortification wall superfluous. The building of the walls aimed at promoting Roman rule and inspiring the city’s residents, who had come from walled urban centers and smaller settlements from the greater area, with a sense of safety and social cohesion.

Throughout the entire length of the wall, five gates have been identified until now: the Northwest, the West, the Southwest, the Southeast, and the East. Two postern gates have been found, one in the west part of the north wall (no. 10)and a second one in the north part of the east wall (no.?), and there must have been gates at other points, e.g. the end of the cardo that passed in front of Basilica B (no. 58). With the exception of the monumental triple West Gate, the other gates were similarly configured: an arched opening framed by two semicircle towers.

The West Gate, whose (partially-buried) ruins may be made out today, was the city’s main—and most impressive—entrance. It was here that the road beginning from the port on the Ionian coast concluded, and it was here that the city’s main avenue (decumanus maximus) began, passing through the city along its transverse axis and bringing visitors to its center. The gate, which had three arched openings (a center one for wheeled vehicles and two side ones for pedestrian traffic) was flanked by two semicircle towers, of which that on the north remains preserved to an appreciable height. Based on excavations in the area, the pipe of the Aqueduct, which then continued to the south on piers, passed above this gate. The triple gate depicted on coin issues of the Hadrianic age has been identified as the West Gate. The West Cemetery extended out beyond this gate.

The Northwest Gate was the starting-point for an important paved N-S road which crossed the adjacent North Cemetery and then the Suburb (Proasteion) before in all likelihood ending up at the Victory Monument. The gate, which is 4.60 meters wide, is reinforced on either side by two semicircle towers. Small, offset postern gates ensured access to their interior. To the right and left of the gate, and with a length equal to that of its opening, two very sturdy piers, rectangular in plan and with limestone blocks at their base were formed. The blocks came from older buildings in the greater area. The North Cemetery extended outside this gate.

Another decumanus passed though the East Gate, which after traversing the East Cemetery came to an end on the coast of the Ambracian Gulf. In its initial form, the gate was reinforced by two semicircle towers, which following their destruction were replaced by new rectangular ones, constructed from reused material. Reconstruction was also carried out on the opening of the gate. The East Gate’s proximity to the Ambracian coast and the level ground outside it made it especially useful—as well as very vulnerable, as shown by its complete destruction and reconstruction.

The road that led to the main port at Vathy (Vathi) started from the Southeast Gate, at which one of the city’s cardines concluded (it partly coincided with the contemporary Via Egnatia from Ioannina-Preveza). This gate too was flanked by two semicircle towers. The better-preserved east tower preserves an offset arched postern that led to its interior. A built staircase in contact with its east wall secured access to the rampart-walk. Annexes north of the tower are interpreted as a guardhouse and quarters for the staff. Most of the tower is now destroyed. Inside both towers there were found many terracotta plaques that had been used in paving the floors in a herringbone pattern (opus spicatum). Excavation in the gate area has revealed part of the South Cemetery.

The construction features of the other gates are recognizable at the Southwest Gate, which is fragmentarily preserved. Of the west tower, part of the west wall, the genesis of the arch, and three steps from the brick staircase at its northwest corner survive. A postern gate led to its interior. The tower was later rebuilt of material in second use, and acquired a rectangular ground plan. Repairs and alterations were also found on the east tower. On the interior and parallel to the wall in the gate area, the piers of the Aqueduct can be made out.