The House of Manius Antoninus

The House of Manius Antoninus

There was a luxurious urban house (domus), known as the House of Manius Antoninus, about 300 meters northeast of the Odeum and 60 meters from the west wall of the Early Byzantine fortifications. The house has been excavated over an area of about 3400 square meters. Its width encompassed that of a building block (approximately 57 m.), while its length remains unclear. Its name is owed to one of its owners who renovated it in the late 3rd-early 4th century AD.

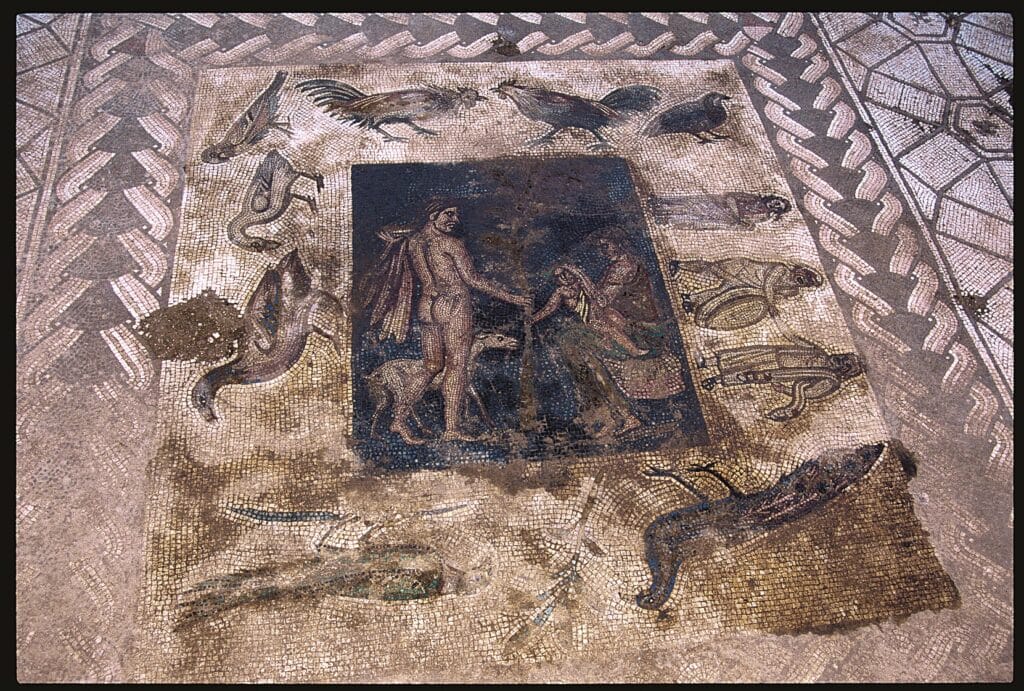

The house belonged to the so-called “developed type” of Roman urban residences, with an atrium and peristyle as we know them from cities in Italy as well as the Greek region. Two of the city’s cardines formed the east and west boundaries of the house. It had at least three entrances. The entrance led to a peristyle courtyard (peristylium) with an outdoor garden and paved porticos, at least on the north and west. Along the north side of the courtyard there were four rooms, three of which (1-3) were probably bedrooms (cubicula). They had mosaic floors featuring geometric and vegetal ornaments. The floor of the fourth room, which was a dining-reception room (triclinium) was decorated with an elaborate mosaic composition with interlocking dodecagonal designs and an off-center emblema with a scene from the life of the god Dionysus. The composition was framed by a guilloche and wide band with a scene from a satiric drama on the north and various birds on the other three sides. South of the peristyle courtyard, an open area was probably a garden (viridarium), and the remains of walls surrounding it point to the presence of a second peristyle.

The installations of the house’s balneum-baths extended north of the above two peristyles. The rooms in the balneum were organized around a spacious hall and included smaller heated and unheated rooms, bathtubs for hot (caldarium), tepid (tepidarium), and cold (frigidarium) baths, as well as a changing room (apodyterium). At the west and east ends of the complex and at a lower level was the combustion chamber (praefurnium) and boiler room required for the hot baths, which had additional under floor and wall heating, like large public baths.

West of the baths was an atrium, i.e. a covered space with a large rectangular opening in its roof (compluvium). On the floor beneath this opening was a shallow cistern (impluvium) in which the water that fell from the roof was collected. North and west of the atrium, which also functioned as a light well and ventilation system for the house, extended a series of rooms and ancillary spaces having various uses.

The wing which unfolded south of the atrium and west of the garden formed the “heart” of the house. It was accessible not only from inside but from outside the house, from the main entrance on the south side (IB), which has not been identified.

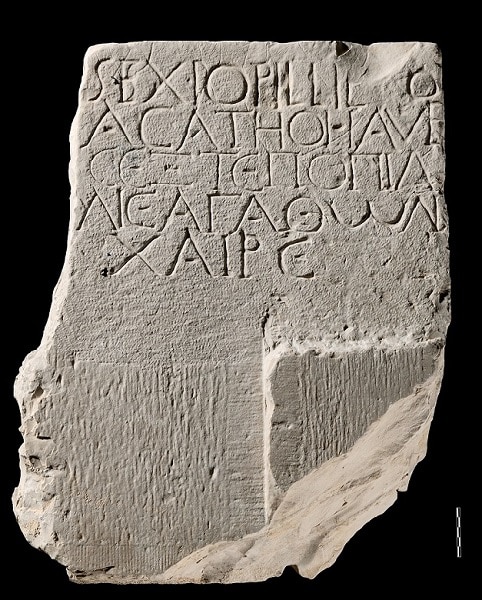

An oblong room (alae) in which fragments of a mosaic floor with geometric designs survive led on the north to an open-air courtyard and on the east to a vestibule and spacious dining-reception room. The mosaic composition on the floor of the vestibule included the founder’s inscription of Manius Antoninus in a circle: Μάν(ιος ή -ίλιος) Ἀριστοκλίας. Εὐτυχίτω ἡ τύχη τῆς οἰκίας, εὐτυχίτω καὶ ὁ ἀνανεωτής τῆς οἴκο(υ) / Μάν(ιος) Ἀντωνίνος, μετά της Θεοσήγου. According to the inscription, Manius Antoninus and his wife Theosigos were the renovators of the house. The inscription, which dates to the late 3rd-early 4th century AD, was surrounded by stylized vegetal and geometric motifs, while in its center a medallion was formed with the “knot of Solomon”, a symbol of the alliance, relationship, and union of the divine with the human.

The northwest corner of the courtyard was taken up by an elevated space accessible via steps that had a mosaic floor. Perhaps the cult of the Lares, the household gods, was practiced here. Further north was the tablinum, the master’s office, where he received his clients, closed agreements, and learned the day’s news. On the west this room communicated with a triclinium.

As may be seen from the dating of the floor mosaics, the construction of the house dates to the early 2nd century AD, a period when Nicopolis was at its zenith. Later, in the mid-3rd or early 4th century AD, the house experienced a second building phase in which according to the founders’ inscription it was renovated with adjustments, additions, interior alterations, and extensions. The entirety of the finds, however—above all, the pottery—encompasses a broad chronological framework of about five centuries (1st-5th c. AD).