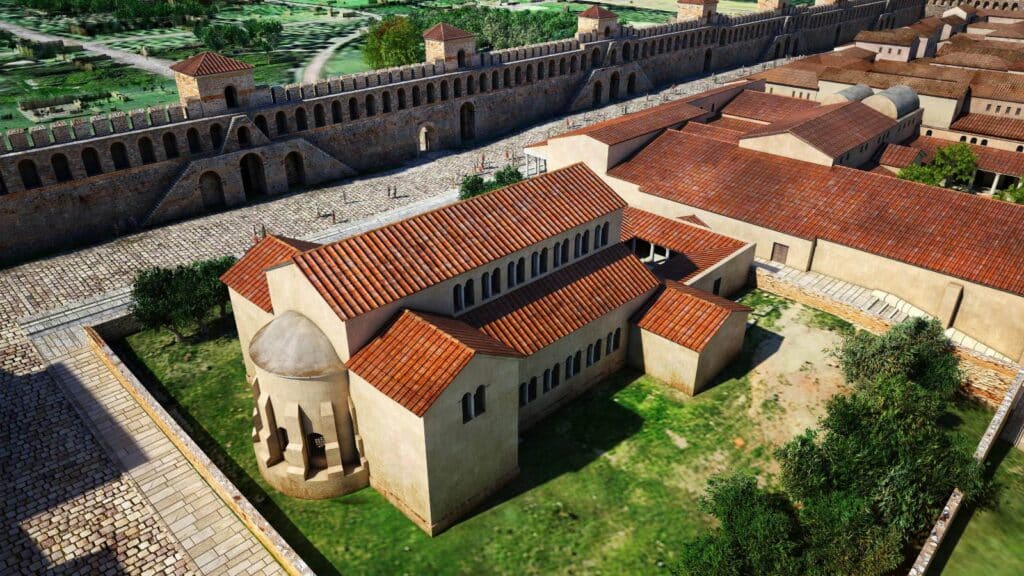

The predominance of Christianity and the consequences of the barbarian invasions which began in the 3rd century AD and continued during ensuing centuries also exerted a direct influence on Nicopolis’s civic landscape. The houses of worship for the new religion, which were the center not only of religious but of social and political life as well, took up a significant part of the urban area with their size and bulk.

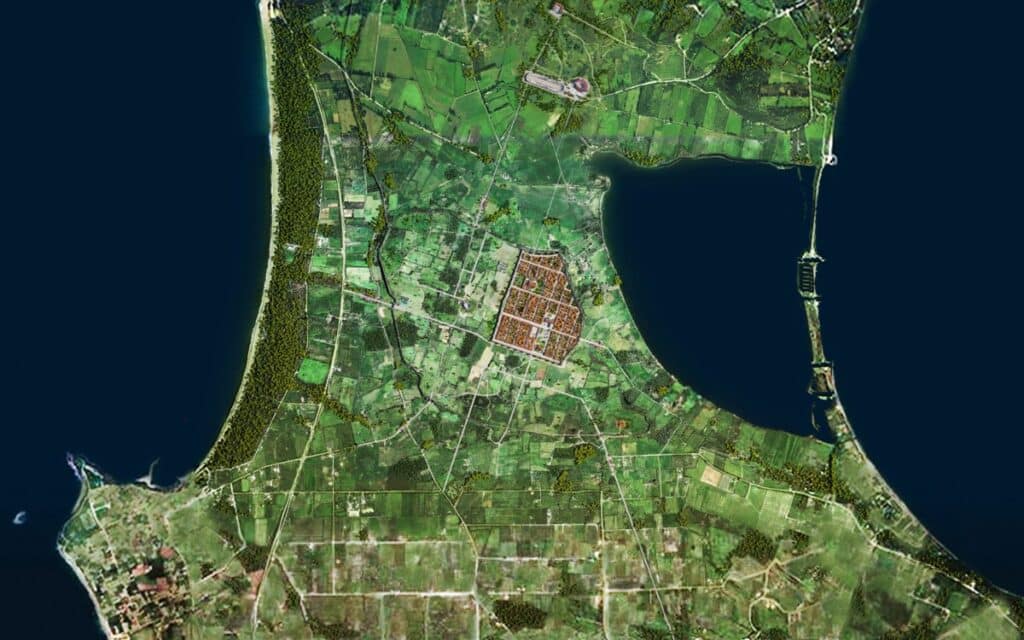

The Herulian invasion in the mid-3rd century AD demonstrated the weaknesses of the Augustan fortification wall. A reassessment of the functionality of the fortifications following the city’s occupation by the Vandals in 474 led to a reduction in the wall’s perimeter and reorganization of the urban area. The Early Christian city was limited to the northeast sector of the original (Roman) city plan, occupying an area of about 274 stremmata (27.4 hectares), i.e. one-fifth of the area enclosed by the Roman walls.

The choice of location within which the Early Christian city was confined appears to have been determined by specific reasons. The site’s geographic advantages probably took precedence over preserving the public buildings of the Roman age, which fell into disuse when Christianity prevailed. For example, the area where the center of the Roman city (the Forum) with important buildings like the Odeum had been located remained outside the new fortifications. The section chosen to create the new city was near the fish-breeding Ambracian Gulf, the primary source of wealth for Nicopolis and a communication route to inland Epirus. Furthermore, access by road to the city’s large port on the Bay of Vathi was relatively easy via the southeast gate of the Roman fortifications. The harbor settlement apparently flourished during Early Christian times, as shown by the remains of a magnificent basilica at the site of Agios Minas (Menas) on the east side of the bay.

The source of water which flowed on the slope below the house (domus) of the ekdikos Georgios was certainly an advantage in the choice of site. An additional reason was the fact that the terrain in this part of the city, which presents a gentle N-S decline, facilitated the natural flow of waste into the sewers. This waste must have ended in the lagoon of Mazoma, whose coastline was many meters further west, as geophysical investigations in the 1990s showed. Finally, it is possible that the insignificant number of ancient religious buildings in this area of the city in relation to others may have played a role in the choice of site.

The precinct in the sacred grove of the suburb, as in the original city plan, remained outside the fortifications. With the abolition of athletic games throughout the empire, the monuments of the suburb were abandoned. The new walls, the buildings for Christian worship, and the so-called “Nymphaeum” are the main visible remains of the Early Christian city.

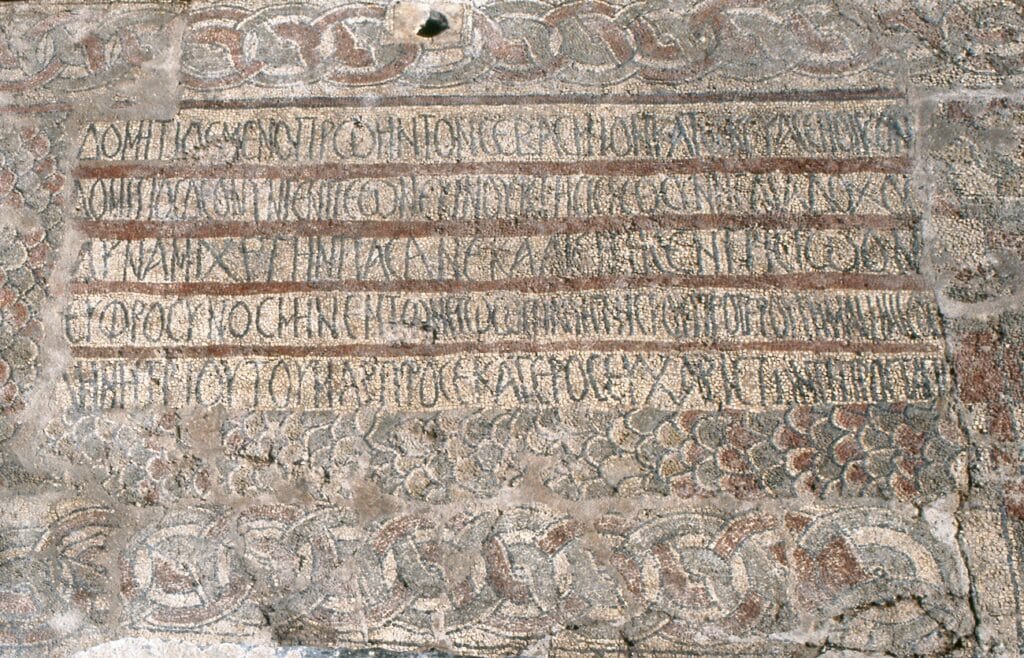

The evidence at our disposal about the urban fabric and private residences of Early Christian Nicopolis is limited. Generally speaking, it appears that the orthogonal Roman town planning system was retained, though it probably became denser. The plans of two of the four basilicas found inside the wall, Basilica A (of Dometius) and Basilica B (of Alkison) were adapted to the ancient Roman plan, since their main entrances on the west were on N-S roads (cardines) laid out by the Romans. Two of the three identified gates also coincided with the original road axis. The so-called “Beautiful Gate” in the south wall lay on the axis of the cardo which passed by west of Basilica A. However, the axis of the main gate in the west wall was not on the axis of the road laid out by the Romans. It is possible that for reasons having to do with adaptation to the terrain, the Roman road had deviated at this point from the strictly geometric plan. The east gate of the Roman fortification wall, which led to the coast at the lagoon of Mazoma, was rebuilt and continued in use during Early Christian times.